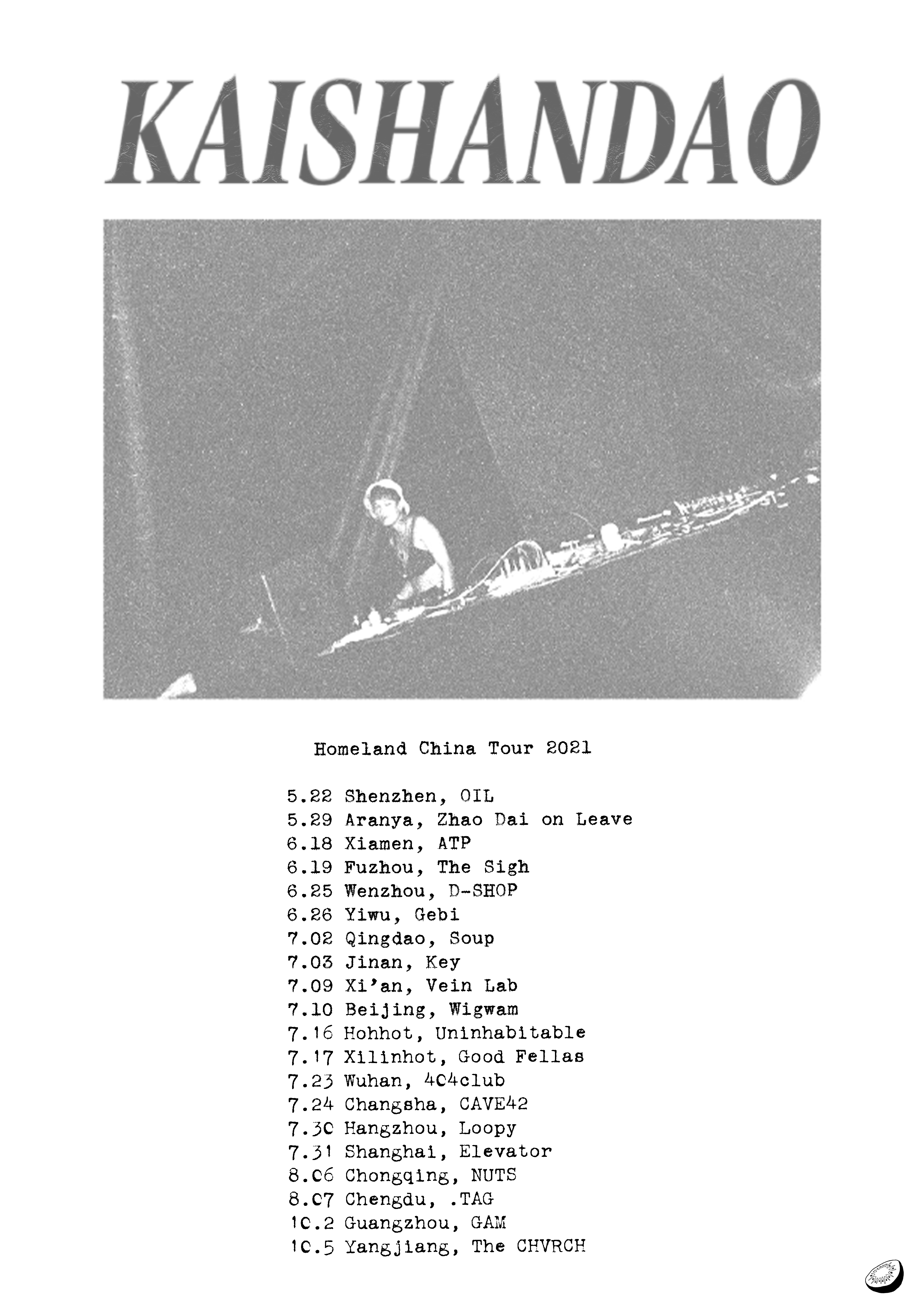

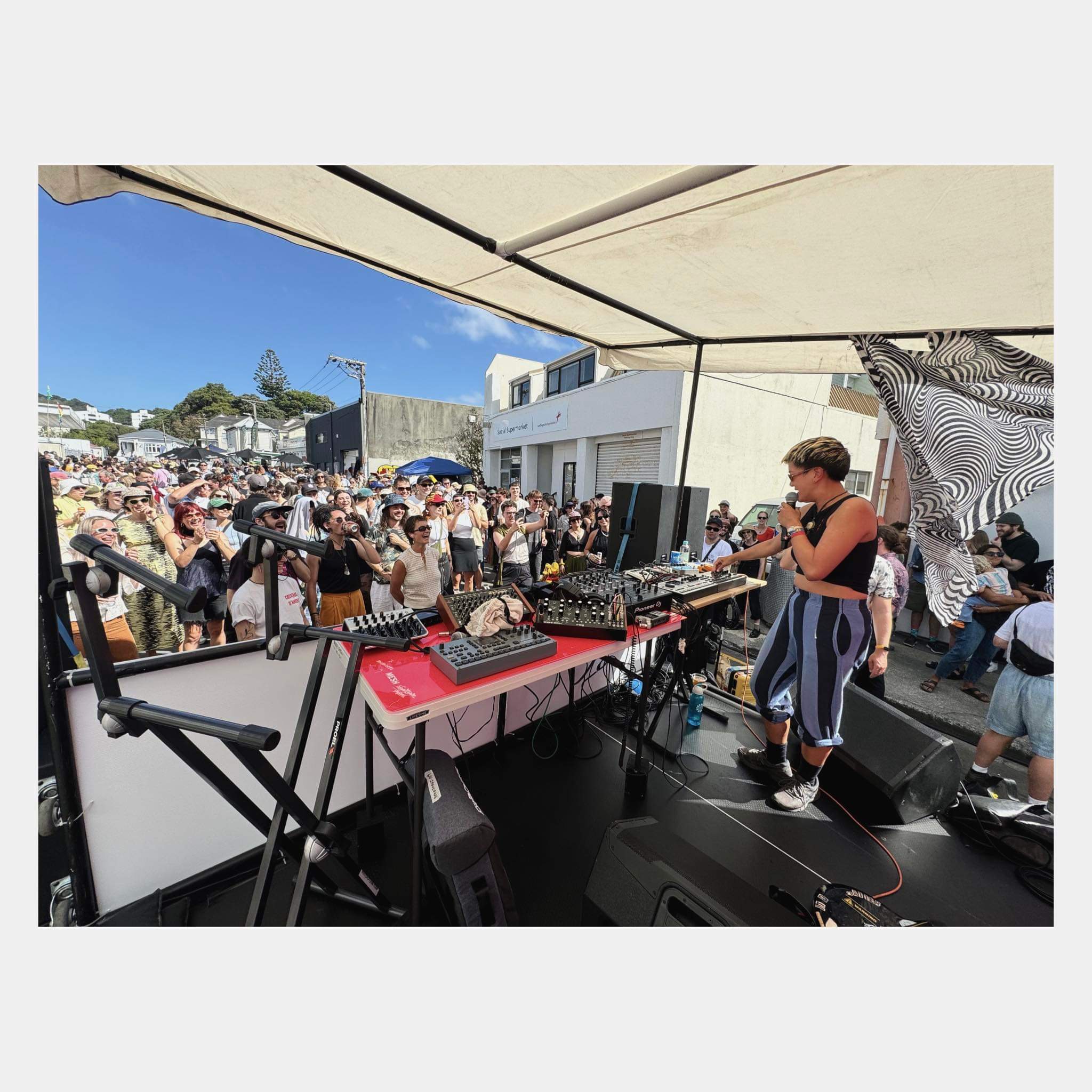

Kristen Ng (she/her) is a musician, writer and event organizer based in Chengdu, China. She performs and produces electronic music as Kaishandao. Kristen is the founder of the NZ-China media platform and touring agency Kiwese and online radio station cdcr.live, with a focus on live performance, documentation and cross-cultural collaboration.

Kristen was born in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Aotearoa, with ancestral roots in Taishan, Guangdong.