Music’s Environmental Impact

Music and ‘the environment’ have a complicated relationship. Search those two words on YouTube and mostly you’ll find hours-long tracks of relaxing nature sounds, and perhaps a few ‘awareness raising’ songs and playlists about environmental issues (most of which kind of suck). Keep searching and you’ll see that music and the environment is a topic that’s growing in popularity, with articles about things like music’s power to inspire and educate, short histories of the role of music in environmental activism, and projects to help musicians be better environmental stewards – indeed, it’s a whole field of academic study: ecomusicology.

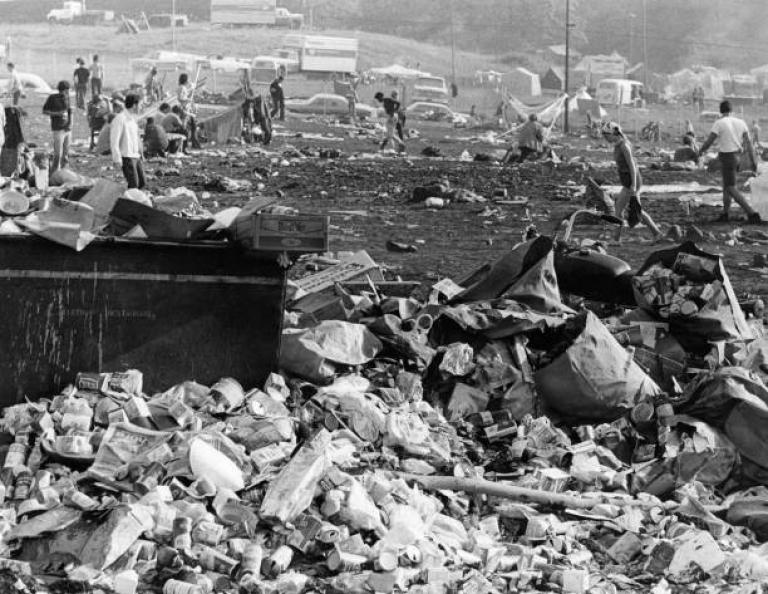

The environmental harms of the music industry have come under increasing scrutiny. Researchers have analysed (and provided recommendations to reduce) the carbon footprint of live music and touring; the impacts of mass produced records, devices, instruments and equipment; the massively energy-intensive data servers required for streaming; the well-established ‘throwaway’ festival scene; and more.

The real-world biophysical impacts of musical activities disrupt the romantic idea of music as somehow immaterial and ethereal. Studies on the environmental impact of recorded music formats, like Kyle Devine’s book Decomposed, show that even the shift from physical records (vinyl, cassettes and CDs) to digital files has not reduced recorded music’s material impacts, but simply relocated those impacts (from plastic products to devices, data servers and other digital infrastructure). This has enabled continued extraordinary growth in consumption of recorded music, outweighing any reduced impacts from digitisation.

The production and manufacture of musical instruments/equipment also follows consumerist economic incentives. Like most products in today’s economy (except expensive and uncommon ‘quality made’ products), musical instruments and equipment are generally not designed for easy repair or durability, and often have in-built planned obsolescence, particularly electronic equipment (see books like Digital Rubbish and The Anthrobscene for more detail on the e-waste catastrophe). The mass production of musical instruments depletes natural resources and even threatens certain species, and requires vast quantities of non-renewable and toxic materials (e.g. fire resistant additives in electrical equipment). While artisanal instrument craft and repair practices still exist and are highly valued, they are crowded out of the mainstream and risk becoming inaccessible and elitist compared with low-cost goods (likely cheap because people and the environment are exploited across the supply chain).

The point of such research isn’t to show that music is inherently unsustainable – it’s not. The blame for the pollution and degradation of the natural world lies squarely at the feet of our hyper-consumerist, exploitative, growth-based global economic system (and subsets of this such as ‘petro-capitalism’), along with the anthropocentric, Eurocentric cultural systems, values, beliefs and ideologies that perpetuate the modern economy. But like any industry or profession, music cannot escape the broader context it exists within, and so, modern music-making activities inevitably generate unsustainable and unsafe levels of greenhouse gas emissions, waste and pollution.

The music world has mounted some notable responses to these challenges: bands and musicians (like Coldplay, Formidable Vegetable and Greta Thunberg’s opera singer mother, Malena Ernman) rethinking touring and flying because of the climate impact; foundations and organisations (e.g. EarthPercent, Julie’s Bicycle, Green Music Australia) established to support the music industry to reduce its ecological footprint; concerts like Live Earth and Climate Live to raise money and awareness for the climate crisis.

But when it comes to music’s environmental footprint, the impact of the materials we use to make music – instruments and equipment – receives very little attention. And yet, addressing this aspect of music’s environmental impact arguably requires and inspires more creativity than any other.

A resourceful music practice overturns the consumerist model by taking the unsustainability of the modern economy and music industry as the starting point without compromising creativity. Its underlying premise asks: what if, instead of continually purchasing and consuming new records, devices, instruments, pedals, amplifiers, gadgets etc., we could fulfil the desire for new sounds and musical possibilities by using only the materials already available to us, and bringing in new materials only when they have minimal environmental impact? Limitations and boundaries are widely accepted to enhance creativity – why not apply ecological and planetary boundaries to musical creativity?